It appears that humanity is fated to never catch a break in this decade.

First it was the COVID-19 pandemic, then the Ukrainian Crisis, global inflation, monkeypox and now food shortages.

If you’re already complaining that things are getting expensive, then prepare to complain more, because even your chicken rice isn’t spared.

Malaysia Cutting Off Chicken Exports

On late Monday (23 May), Malaysian Prime Ismail Sabri Yaakob announced that the chicken exports, totalling up to 3.6 million chickens a month, will be halted from 1 June onwards.

The impetus behind the decision is to stabilise the domestic prices and supply of chicken within Malaysia, which was initially prompted by complaints from Malaysian citizens.

Malaysian customers have been complaining about the rising chicken prices, such that some retailers are even resorting to rationing their sales.

Hence, this issue was brought up in a meeting with Malaysia’s Agriculture and Food Industries Minister that Monday.

By shorting the chicken exports, it means that more chicken products will be available and circulating within domestic borders, which serves to bring down the price by increasing the internal supply, thus serving the best interests of its citizens first.

The poor supply of chicken has been happening since the start of the year.

The Malaysian authorities have also simplified the subsidy claim process for chicken produces to help mitigate the rising costs of production.

Backtracking to Economic Policy

With regards to the subsidies for poultry farmers, it came about at first when Malaysia imposed a ceiling price of RM8.90 per kilogram for chickens ever since 5 Feb.

However, owing to this price ceiling, it means that chicken sellers have no right to decide on how expensive they think the chicken should be.

For the most part, product prices tend to be controlled by market forces. With the government intentionally intervening for the sake of the consumers’ welfare, the sellers will inevitably suffer some losses.

Hence, it made some chicken breeders lament because it cut into their profit margins sharply after facing in the rising production costs.

In order to compensate the farmers and encourage more production, Malaysia’s Agriculture and Food Industries Ministry has offered a RM279.43 million to help the chicken breeders through the Keluarfa Malaysia Maximum Price Control scheme.

Through the subsidies, the government take up a portion of the cost of the production and made the whole production more financially manageable.

Factors Causing the Rising Cost of Production

Not to sound like a broken recorder, but the war between Russia and Ukraine has a huge ripple effect—resulting in the rise in energy prices and the decrease in wheat supply.

This, in turn, affects everything from the raising of livestock, packaging, and transportation.

For instance, hatcheries need a constant amount of feed, electricity and heating for the incubation period.

It is a costly operation due to its energy needs, only worsened by the Ukrainian crisis as Russia happens to be the second largest oil-producing country besides the coalition of oil-producing countries in the Middle East (OPEC).

Since the costs have gone up, the hatcheries pass on the burden of cost to the farms by rising the prices of the chicks that they sell.

No matter how much farms have shifted to renewable energy by installing solar panels or resorted to more energy-sustainable methods of raising the chicks, it doesn’t discount the fact that they’re still partially reliant on traditional sources of energy—the burning of fossil fuels—and electricity prices per kilowatt have increased in varying degrees in different countries since last year.

No country has been left untouched because of our heavy dependence on electricity.

Then there are the costs of gas containers used for heating sheds, and Russia is the second-largest producer of natural gas, behind the United States.

To lay down the foundation for the next few points, energy is required in every part of the supply chain. Therefore, increasing energy prices in general means every part of the chain suffers.

Farms specifically use borehole water, but the costs of chemicals to sanitise the water has increased by 30%.

Additionally, different types of feeds and ingredients are necessary to keep the livestock in good health, typically wheat and/or soya.

With Russia announcing an export ban on wheat, it has caused prices to skyrocket further, if the Ukrainian crisis and the country’s inability to ship out any goods hadn’t already made the prices soar in the first place.

According to Germany’s Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control, Ukraine’s wheat production accounts for 11.5%, whilst Russia produces 16.8% of the global export supply.

In total, nearly one-third (28.3%) of the global wheat supply is no longer easily accessible, while the demand for the agricultural products has not diminished in the slightest.

Prices for feed have never been higher.

Lastly, there is transport.

The chickens need to be transported in crates by trucks, but the cost of fuel has also surged.

Everything has become more expensive.

The only thing that that supplier of various products can do to cope with the rising costs is to shift the burden to the buyers, and that amount slowly accumulates until we, the final consumers, can visibly notice the price hikes in goods.

Food Nationalism at its Finest

Generally speaking, Malaysia isn’t the first country to implement a food export ban.

Part of the reason why wheat prices took such a beating was also because India banned exports of staple cereal.

The Indian government had come to that decision after a terrible heatwave that caused droughts and bad harvests all over the country, thus driving the domestic prices to record high.

Whereas for the other main producers of wheat, they had to tangle with droughts and floods too.

In a nutshell, with or without the Ukrainian crisis, the agriculture sector isn’t having its best year with the havoc that climate change is wreaking.

Food prices were bound to rise, to speak nothing of the global inflation that was pressured by the two-year-long pandemic.

Besides chicken, Malaysia has abolished the approved permits for cabbage and evaporated milk.

Judging from past food crises, economists believe that more countries will follow suit, which will exacerbate the problem, as well as inflate food prices further.

However, export restrictions are usually temporary in nature, wherein the country chooses to stabilise their own domestic situation first and ensure that their people are fed at reasonable prices before they begin to tackle global demand.

For Singapore, a small country whose economy is highly dependent on both imports and exports, it’s bad news for us overall.

The Effect of the Export Ban on Singapore

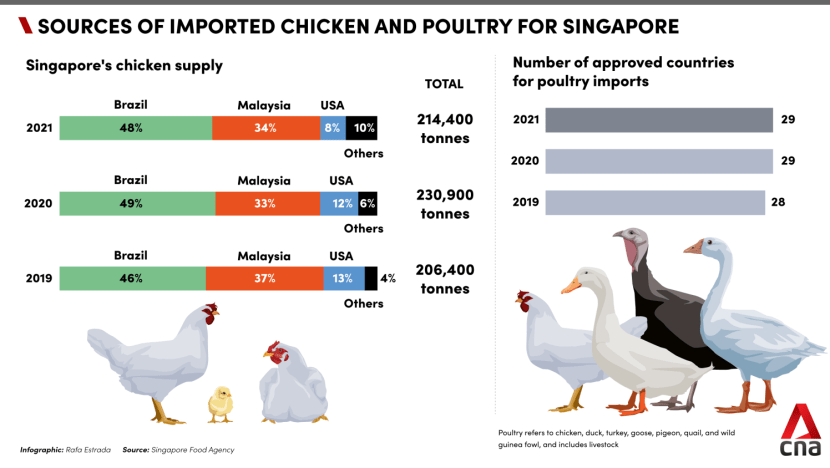

According to the Singapore Food Agency, Malaysia accounts for 34% of Singapore’s imported chicken.

Brazil takes up the majority with 48%, while the US and other countries take up 8% and 10% respectively.

However, the statistics given by the Singapore Food Agency doesn’t distinguish between chilled chicken and frozen chicken.

Chilled chickens are the freshest batch; the chickens tend to be delivered to Singapore alive, before they are slaughtered, chilled, and sold.

Frozen chicken has a longer shelf life by virtue of it being prepared and the temperature it’s kept under.

The former tends to come from butchers at wet markets or straight from the suppliers themselves to the restaurants/eateries, while the latter is the sort that FairPrice or any other supermarket chain tends to provide in their poultry section.

When the Malaysian chicken export ban was announced, the price increase in chicken was immediate.

By Tuesday, the price of a chicken per kilogram had hiked up by $1.20.

When the export ban sets in officially on 1 June, chicken prices can be expected to double or triple.

Measures to Negate the Effect

How different eateries or restaurants cope with the price hikes varies.

Small players such as local business Naked Chicken, which sells home-style fried chicken in limited quantities every week, have decided to close temporarily.

In a recent Instagram post, the small eatery said that it will stop operating indefinitely on 30 May as a direct consequence of the temporary Malaysia export ban.

Other restaurants are scrambling to find new suppliers or have suppliers who already trying to diversify their sources.

Alas, sentiments are mostly pessimistic.

Veteran chef Damian D’Sliva, the owner of a multicultural, heritage cuisine restaurant called Rempapa in Paya Lebar, expresses his helplessness towards the situation.

Most of his signature dishes like nasi lemak, chicken curry and debal chicken require fresh chicken from Johor, but he’s aware that he’ll have to switch to frozen chicken if the push comes to shove.

Chef D’Sliva knows that the freshness of the poultry will affect the taste, but it’s a flaw that he has to accept until the export ban is lifted, since it’s difficult to transport live chickens over long distances.

Even in the best-case scenario where the suppliers manage to find a reliable, alternative source for chilled or frozen chicken to make up for the sudden deficit, it will still take a longer period of time for the goods to arrive, as opposed to getting the raw ingredients straight from a neighbouring country.

Many hawker centre stalls are expecting their business to drop by a wide margin. Some might choose to increase the prices on their menus, while others might decide to absorb the additional costs instead.

Just don’t be surprise if you see tape over LED-lit boards, stating new prices for items with chicken on them, or just a blatant “Not Available”, because the stalls legitimately have nothing to offer.

Restaurant owners can also substitute chicken with other kinds of meat, but the alternatives are expensive too.

The Possibility of a Chicken Cartel

To make matters worse, it’s suspected that there is a chicken cartel in Malaysia, who are businessmen who are colluding together to drive up and control the price of the chicken.

Presently, the Malaysian Competition Commission is investigating reports about cartels controlling the price through output among the larger companies.

Mr Ismail promised that if the rumours are proven to be true, and those companies are purposely sabotaging the supply for their own profit, they will be appropriately punished.

The Consumers’ Affairs Industry declared that they will be taking legal action, should it be necessary. The investigations will only conclude at the end of June.

It is likely that the theory is true, as state news agency Bermada noted that there has been a shortage of locally produced poultry as cartels stopped their farming operations.

Truth to be told, the situation in Malaysia itself is quite dire.

Ameer Ali Mydin, the managing director of Mydin chain hypermarket and retail outlets in Malaysia, remarks that based on weekly orders, they typically require 100 tonnes of chicken for all outlets, but now it has fallen to 40 tonnes.

Smaller retailers are receiving less as well.

In hindsight, the chicken export ban was a matter of time.

No one knows how long it will last though.

Featured Image: Shutterstock / JKuy